The leaf entered for the seventh time. March 11, 1945. Sing Sing Prison, D Block Corridor. 2:17 pm

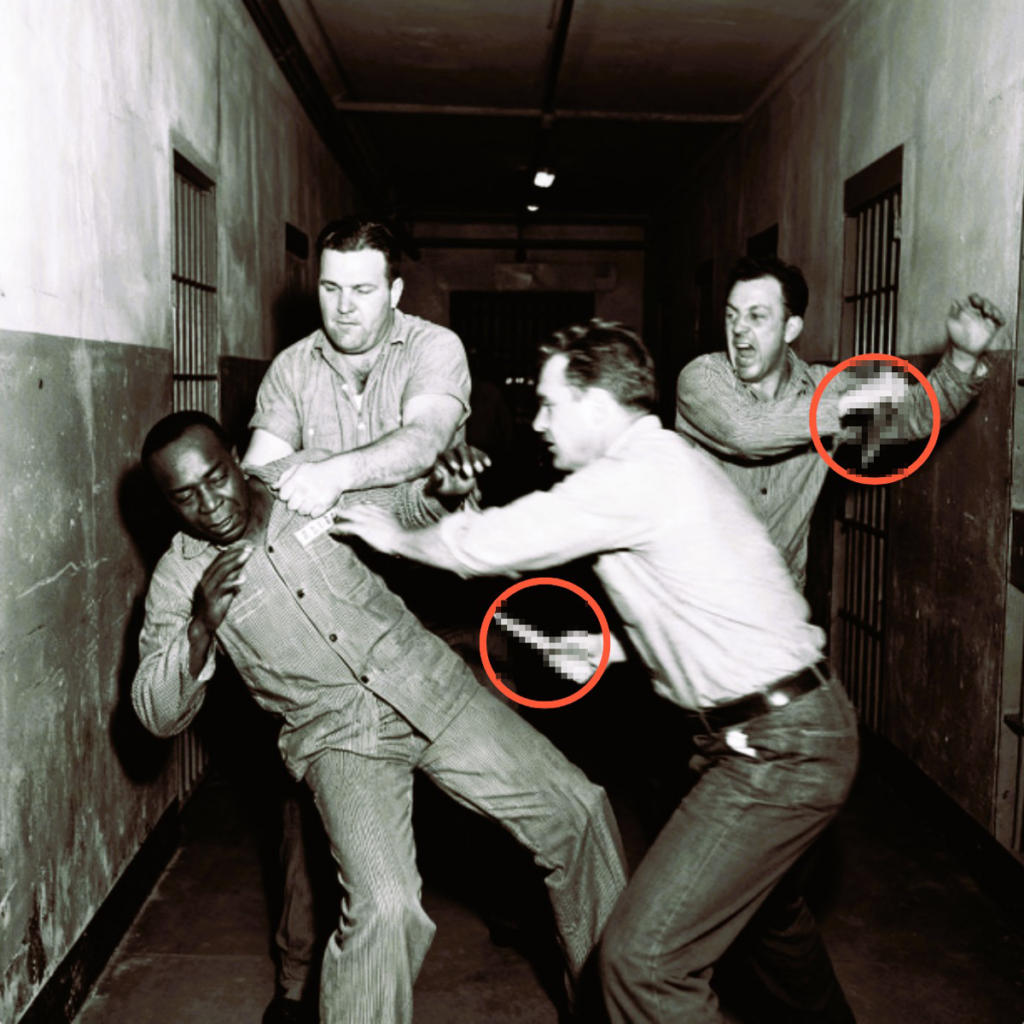

Bumpy Johnson lay on the ground, blood spreading across the concrete like spilled paint. Three Italian prisoners stood over him: Tony “The Blade” Marquez, Vincent Callo, and Sal Romano. They were all breathing heavily. They each held makeshift bladed weapons they had sharpened for weeks in the machine shop.

Seven stab wounds: abdomen, chest, back, lung. Each one placed to kill. The corridor fell silent. Sixty inmates watched from their cells. Guards rushed toward the scene, blowing their whistles. But for a frozen moment, they all just stared at Bumpy Johnson lying in a pool of his own blood, his prison uniform soaked, his breathing shallow and wet.

Tony leaned in and whispered into Bumpy’s ear:

—Luciano sends his regards. Harlem is ours now.

Bumpy’s eyes were open; he was still conscious. His lips moved, trying to form words, but only blood came out. He coughed, a horrible gurgling sound that made even the most hardened criminals look away. Tony laughed, stood up, and wiped his razor blade on his prison pants.

“It’s over. Let’s go.”

The three Italians walked away, calm, confident. They had just killed the king of Harlem in front of 60 witnesses. The guards reached Bumpy. One of them took his pulse, his hands trembling

—He’s still breathing. Get a doctor, now!

Bumpy was carried to the infirmary on a stretcher. His blood left a trail down the corridor. The prison doctor examined Bumpy and shook his head.

—Seven wounds, two in vital organs, punctured lung. He has lost at least three pints of blood.

He looked at the warden.

“I’ll try, but he has maybe six hours left, eight if he’s lucky.”

Tony, Vincent, and Sal celebrated in their cells that night, passing around bootleg whiskey, laughing at how easy it had been. They had 72 hours before they realized their mistake. Because Bumpy Johnson didn’t die, and the three men who tried to kill him were about to wish they had succeeded in killing themselves.

To understand what happened next, you need to understand who these three men were.

Tony “The Blade” Marquez was the leader. Thirty-four years old, an initiated member of the Luciano family, serving a 15-year sentence for armed robbery. Inside Sing Sing, Tony was royalty, protected and feared. He had killed two men in prison. Both cases were ruled self-defense because the Italian mafia had bribed enough guards to ensure Tony’s story was always believed.

Vincent Callo was the muscle. 6’3″ (1.90 m), 240 pounds (108 kg), a former boxer, serving 20 years for manslaughter. Vincent had sent seven men to the Sing Sing infirmary in his three years inside. Nobody messed with Vincent.

Sal Romano was the quiet, reliable one, serving 12 years for extortion. He worked in the prison laundry, kept his head down, and followed orders. When Tony and Vincent needed a third man they could trust, Sal was the obvious choice.

These weren’t random criminals. They were professional killers, and they had just stabbed Bumpy Johnson seven times with surgical precision. Except they had made a critical mistake. They had assumed that seven stabs would be enough.

Bumpy was walking from the library back to his cell. 2:15 pm Shift change. The corridor was crowded with inmates, but no guards. Tony stepped forward. Vincent and Sal flanked him. Three men blocked Bumpy’s path. No one helped. This was prison justice.

“You know why we’re here,” Tony said, pulling out his knife.

Bumpy’s voice was calm.

—Luciano is afraid of a man in a cage.

—Luciano is intelligent. You’re a problem, so we’re solving it.

They didn’t give Bumpy a chance to defend himself. Vincent grabbed Bumpy from behind. Sal came from the side, and Tony went for the kill.

First stab: abdomen. Second stab: chest. Third stab: back, between the ribs. Bumpy fell to his knees. Fourth stab: shoulder. Fifth stab: side. Sixth stab: back again. Bumpy collapsed forward onto the concrete.

Tony leaned over and delivered the seventh stab right in Bumpy’s back, at an angle towards the lung.

“Harlem is ours now,” he whispered.

Then they walked away.

Dr. Harrison worked on Bumpy for 3 hours, suturing the wounds and stopping the bleeding where he could

“He should be dead by now,” Dr. Harrison told the warden. “But he won’t make it through the night.”

Bumpy was taken to the hospital wing. Hour one: unconscious. Labored breathing, gray skin. Hour six: still unconscious. Dr. Harrison checked him, expecting a corpse; his heart was still beating. Hour 12: Bumpy opened his eyes, unable to speak, but conscious. Hour 24: Bumpy was still alive.

Tony was getting nervous. He’d heard Bumpy was still breathing, but Tony reassured himself. Seven stab wounds, punctured lung. The doctor said he’d die. Vincent and Sal weren’t worried. They were protected by the power of the Italian mafia. They had no idea what was coming.

Here’s what they didn’t understand about Bumpy Johnson: Being weak and looking weak are two very different things. Bumpy was in that hospital bed barely able to breathe, but his mind was working. And in Sing Sing, Bumpy had something the Italians didn’t: the respect of the invisible people; the Black porters, the kitchen workers, the laundry workers, the janitors.

Bumpy had spent 18 months treating them like human beings. And now, lying in that hospital bed, he collected those debts. A porter named James visited Bumpy at the 36th hour. Bumpy whispered something. James nodded and left.

Vincent was descending the metal stairs from the third floor. Normal routine. He’d done it a thousand times. But this time, halfway down the stairs, his foot hit something. Industrial grease splattered across three steps, invisible unless you were looking for it.

Vincent’s feet slid out from under him. He tumbled down 20 metal steps. His body hit each step; back, head, and spine slamming against the steel edges. The sound of his body hitting the stairs echoed throughout the cell block. Then, silence.

Then Vincent began to scream. The guards rushed toward him. Vincent was at the bottom of the stairs, his legs bent at awkward angles. But worse still, he couldn’t feel them.

—I can’t feel my legs. I can’t feel my legs!

The prison doctor arrived and examined Vincent. His face paled.

—Spinal cord damage. Severe. He is paralyzed from the waist down.

Vincent kept shouting.

“Fix it! Fix it!”

“I can’t,” the doctor said quietly. “The damage is permanent. You’ll never walk again.”

Vincent Callo, 6’3″, 240 pounds of muscle. A former boxer, the man who had sent seven inmates to the hospital, would spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair. In prison, where a wheelchair meant vulnerability, helplessness; where you couldn’t run, you couldn’t fight, you couldn’t defend yourself. A life sentence within a life sentence.

Sal was working his shift in the prison laundry, operating the industrial press, a massive machine that flattened prison uniforms. Sal was being careful. He had used this machine for eight months without incident. But this time, as he fed a sheet through the rollers, his hand got caught.

It wasn’t accidental. A laundry worker named Marcus had disabled the safety mechanism. So when Sal’s hand went in, the machine didn’t stop. The rollers crushed his hand. The sound of bones breaking was audible above the machine’s screeching. Sal screamed.

The guards turned off the machine and pulled out his mangled hand. Every finger was crushed beyond recognition. Fragments of bone, pulverized flesh.

Dr. Harrison examined her in the infirmary and shook his head.

—The damage is too severe. We need to amputate.

“Just the hand?” Sal asked, his voice trembling.

“I’ll try, but if an infection develops…” he didn’t finish.

Three days later, the infection spread. Gangrene, black flesh creeping up Sal’s arm despite the antibiotics. Dr. Harrison had no choice. He amputated Sal’s entire right arm at the shoulder.

Sal Romano woke up from surgery with only one arm. In prison, where you needed two hands to defend yourself, to work, to eat, to survive. A one-armed man in Sing Sing was utterly defenseless, at the mercy of everyone around him.

Tony was having breakfast in the dining room. Oatmeal, the same as every morning. But this morning, when he swallowed, something went wrong. The oatmeal went down the wrong way. Tony began to choke, gasping for breath, his face turning red, then purple.

The guards rushed to him and performed the Heimlich maneuver once, twice, three times. Nothing. Tony fell to his knees, clawing at his throat, his eyes wide. A guard tried again, four times, five times. Finally, the obstruction was cleared. Tony gasped, drew air in, and collapsed. His heart had stopped.

—Get the doctor!

Dr. Harrison came running, started CPR, chest compressions. 1 minute, 2 minutes, 3 minutes, 4 minutes without oxygen. Finally, Tony’s heart restarted. He was breathing, but his eyes… they were open, but empty, staring into nothingness

Dr. Harrison checked her pupils, he checked her answers.

“No,” she whispered. “No, no, no.”

The warden arrived.

“Is he alive?”

“His body is alive,” Dr. Harrison said quietly. “But his brain… was without oxygen for 4 minutes. That’s too long. The damage is…” He couldn’t finish

Tony Márquez was breathing. His heart was beating, but there was no one home. Brain death. Permanent vegetative state. Tony’s eyes were open, but he couldn’t see. His mouth moved, but he couldn’t speak. He couldn’t think, he couldn’t understand, he couldn’t do anything except breathe and stare.

They put him in a wheelchair, fed him through a tube, changed his clothes when they got dirty, and every day they rolled him to the mess hall for meals. Every inmate at Sing Sing could see him. Tony “The Blade” Marquez, the man who had killed Bumpy Johnson, sat in a wheelchair, drool running down his chin, his eyes vacant and empty; a living corpse, a reminder of what happens when you stab Bumpy Johnson and don’t finish the job.

Hour 72. Warden Miller entered the hospital wing. Bumpy Johnson was sitting on the bed reading, still bandaged, but alive.

“Johnson,” the warden said. “I need to talk to you.”

Bumpy looked up.

—Warden.

—Three men, the same three who stabbed you. Vincent Callo, paralyzed for life. Sal Romano lost his entire arm. Tony Marquez, brain dead, a vegetable. All within 72 hours

“That’s terrible,” Bumpy said. “Prison is a dangerous place.”

—You did this, Johnson.

—Warden, I’ve been in this bed for three days, dying. Remember?

—I know it was you. I can’t prove it, but I know it.

Bumpy left his book.

“Warden, let me tell you something. Those three men stabbed me seven times. They tried to kill me. They almost killed me. And do you know what the worst part was? Not the pain, not the blood. The worst part was lying on that floor bleeding out, knowing they thought they’d won.”

He paused.

But they made a mistake. They assumed seven stab wounds were enough. They assumed he would die. They assumed wrong. And now Vincent will never walk again. Sal will never use his right arm again. And Tony… Tony’s body is alive. But Tony is gone forever. He’s a vegetable. He’ll spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair, drooling, staring into space, while everyone who sees him is reminded of what happens when you try to kill someone and fail

The warden stared at him.

—You destroyed three men.

“I didn’t do anything,” Bumpy said quietly. “But if I had, I’d say this: They tried to take my life. I didn’t take theirs. I took something worse. I took their dignity, their strength, their future. Death would have been mercy. What they got, that’s justice.”

—This ends here, Johnson.

—It’s over, Warden. It was 3 days ago.

Tony Marquez lived for 17 more years. Every day in a wheelchair. Every day fed through a tube. Every day staring blankly into space. Inmates would walk past him in the mess hall and whisper, “That’s what happens when you mess with Bumpy Johnson.”

Vincent Callo served his full sentence, 20 years in a wheelchair, never walking again; released in 1965, dependent on his family for everything, bitter and broken.

Sal Romano learned to function with one arm, was released in 1953, tried to find work, but couldn’t; most jobs required two hands. He ended up begging on the streets, dying from exposure in 1958.

The story spread throughout prisons across America: Don’t try to kill someone unless you’re sure the job is done. Because if they survive, they won’t just kill you; they’ll do something worse—they’ll make you wish you were dead.

Bumpy Johnson was released from Sing Sing in 1947. He walked out on his own two feet and returned to Harlem.

Years later, someone asked him about the stabbing.

“Seven times,” Bumpy said quietly. “I was stabbed seven times. And you know what? If I’d been stabbed eight times, I probably would have died. But they stopped at seven, and that was their mistake.”

“What happened to them was brutal,” the interviewer said.

“What they did to me was brutal. I just made sure the punishment fit the crime. Seven stab wounds, three lives destroyed. That’s not revenge, that’s math.”

In Sing Sing, they still tell the story. They still parade Tony’s wheelchair past the cells during mealtimes. They still use Vincent and Sal as cautionary tales. The lesson is simple: You can stab Bumpy Johnson seven times, but unless the seventh time stops his heart, he’s going to wake up. And when he does, you won’t die; you’ll wish you had.

Next week, the story of how Bumpy stopped Malcolm X’s assassination with a single look. No words, just one look that sent four hitmen running. Remember, Harlem didn’t need superheroes. They had Bumpy Johnson. And Bumpy taught the world that sometimes letting someone live is the cruelest punishment of all.