Dramatized and inspired account of real events.

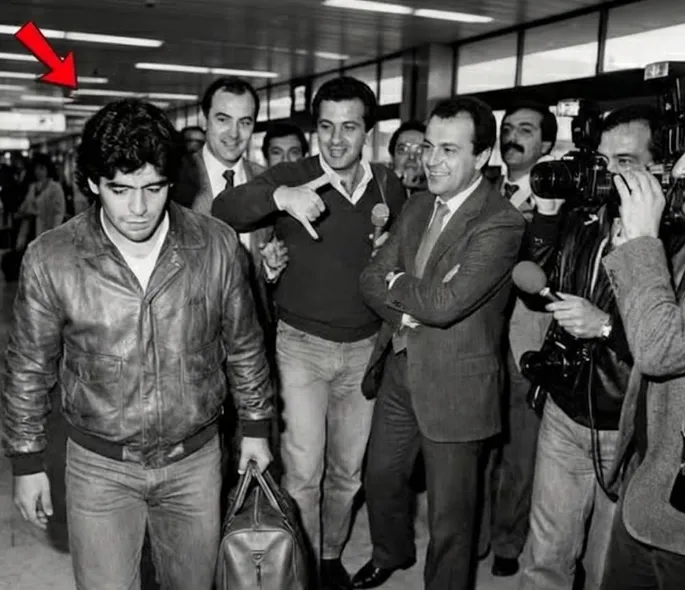

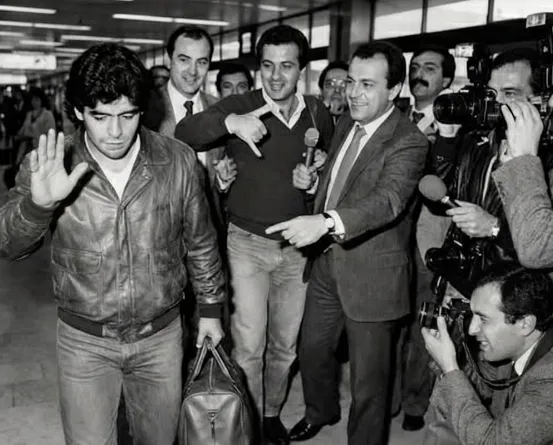

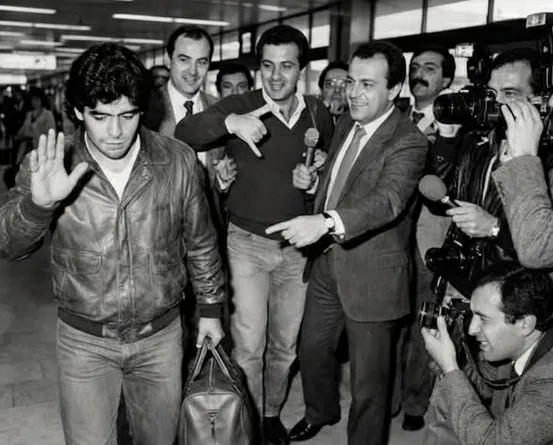

July 1984. Naples Airport. A plane lands. Inside is a 23-year-old man. 1.65 meters tall. Curly black hair, a face like a kid from the neighborhood. Outside, 75,000 people are waiting for him. It’s not a mistake: 75,000 people went to the airport to see a footballer get off a plane.

Diego Armando Maradona has just been bought by Napoli, the poorest team in Serie A. The team from a city that the rest of Italy looks down on. The team that has never won anything. The price: 105 million dollars. The most expensive player in history.

And while the multitude shouts his name, while the celestial flags cover the sky, while Naples explodes, and the port of Italy someone is writing.

A journalist from Milan, gray suit, typewriter, cigarette in his mouth, writes what the whole sport thinks, but nobody says out loud: “Napoli paid a fortune for a player too short, too fat and too South American for Italian football. In three months they will ask for their money back.”

He’s not the only one. Turí says that Maradona won’t survive the Italian defenders, that he’ll split them in two. Roma says it’s a circus, that Napoli bought an expensive clown. Milá says that football is played with legs, or with publicity, and that Maradona’s legs are too short.

Diego doesn’t read the newspapers, but he knows what he’s saying. He always knows. He’s said it all his life: too short, too poor, too much of a slum boy, too much of everything. What an elite footballer should be. But Diego didn’t come to Italy to convince anyone with words.

Naples is a wounded city. The first thing Diego notices when he leaves the airport is the smell: sea salt mixed with garbage, with gasoline, with something he can’t name but recognizes. It’s the smell of poverty, the same smell as Villa Fiorito.

The second thing that sticks are the eyes. People look at him differently here. Not like in Barcelona, where they looked at him with cold expectation, calculating whether he was worth what he cost. Here they look at him with something else, something that resembles despair, something that resembles faith.

Naples is the poorest city in Italy. The port calls it “the shame of the country.” The populi work in the factories of Milan and Turí, where they are treated as second-class citizens. When looking for an apartment in the port, the signs say: “No populi, only dogs.”

The football team is a mirror of the city. Napoli has won a league, it has throughout its history. While Juventus accumulates titles and Milan lifts European cups, Napoli has empty trophy cabinets. The south always loses against the north: in the economy, in politics, in football, in everything.

And now they brought Maradona, the most expensive player in the world, to the poorest team in the league, to the most despised city in the country. Diego understood the weight of that from day one. He didn’t come to play football, he came to change history.

The first leg is at the Sao Paolo stadium. Diego arrives early. The stadium is empty. He walks onto the pitch. He stands in the center of the field. He looks at the empty stands now, but he can see what he’s going to do: 70,000 people screaming, flags, smoke, chants that make the concrete shake. He can see it. He just has to make it happen.

His classmates begin to arrive. Diego observes them. He notices their stares. Some look at him with admiration, others with curiosity, others with suspicion.

The captain approaches. Giuseppe Bruscolotti, 30 years old, 10 seasons with the club, a local hero. He knows this city, this team, and this curse better than anyone. Bruscolotti looks Diego up and down. He’s literally 15 centimeters taller than him. He doesn’t say anything, he just stares. Diego holds his gaze.

After a few seconds, Bruscolotti nodded with a minimal gesture. It wasn’t acceptance, it was something else. It was a “let’s see what you’ve got.”

The training begins. Diego doesn’t speak, he does other things. In the first passing exercise, he puts the ball exactly where he wants, to the centimeter. In the second control exercise, he brings down a 40-meter ball with his chest as if the ball were made of cotton. In the third, a dribbling exercise, he passes to three teammates as if he didn’t exist.

The players begin to look at each other without saying anything. Bruscolotti watches from the side. His expression doesn’t change, but something in his eyes does. When the exercise ends, he approaches Diego again. This time he extends his hand. Diego takes it.

—Welcome to Naples.

This time it is acceptance.

The first official match is against Veropa. Sa Paolo is full, more than full. People are hanging from the railings, sitting in the corridors, standing in any hollow where there’s room for a body. 70,000 people came to see just one thing.

Diego steps onto the field. The noise is palpable. You feel it in your chest, in your bones. He looks around, sees the banners, sees the signs. One says: “Diego, you’re bigger than Jesus.” Another: “Maradona, king of Naples.” Another, simpler one: “Thank you.”

Thank you. He hasn’t done anything yet. He hasn’t gained anything. And he’s already thanking him. Diego says: He doesn’t thank him for what he did, he thanks him for what he represents. For coming here when he could have chosen any other place. For giving them something he hadn’t had for a long time: hope.

The game begins. Veroña’s defenders have clear instructions: mark him hard, or let him turn, hit him early so he knows what awaits him.

Minute 3. The first blow. A defender arrives late to the ball and early to the ankle. Diego falls. The referee calls a foul. He gets up, he says no.

Minute 7. Another blow to the back. He gets up.

Minute 12. The knee. It hurts. He gets up.

The defenders look at each other. Something is wrong. The Argentinian doesn’t complain, doesn’t get angry, doesn’t lose his temper. He just gets up and again.

Minute 23. Diego receives the ball in the middle of the field. Two defenders run towards him. He has no space, no time, but he has something they don’t understand. He touches the ball with the outside of his left foot. A small movement. The defenders adjust, go towards where they think the ball is going, but the ball is already there.

Diego slipped between them. No speed, no power. Just timing, just deception. Now he has open space. He runs. The goalkeeper comes out. Diego raises his head. He sees a teammate alone. He sees the space. He sees the entire play before it even exists. The pass is low. Perfect. Goal.

Paolo explodes, but Diego doesn’t celebrate. He still doesn’t. He just walks towards the center of the field.

Ep Milá, the journalist in the gray suit, is watching the game on television. He watches the play, watches how Diego passed two defenders without running, watches the impossible pass. He doesn’t say anything, but something in his expression changes.

The first season ends with Napoli in eighth place. It’s not a disaster, but it’s not what the city needed either. The sports journalists write: “Was Maradona worth it? The Napoli dream is fading. The most expensive player in the world can’t carry a team alone.”

Diego reads the newspapers now. All of them. Every criticism, every taunt, every prediction of failure. He saves them. Not to respond with words.

In the second season, Napoli finished third. Better, but not enough. People still believe. The streets are still full of banners. The children still go by the name Diego. But there is a question that hangs in the air. Nobody asks it out loud.

What if it doesn’t happen? What if the sport always wins? What if some stories can’t change?

Diego feels that question in the street when people look at him, in the stadium when the team loses, in his head on the nights he can’t sleep. But he doesn’t let it in because he knows something he learned in Villa Fiorito, on the dirt fields, in the matches where there was no referee, no rules, nothing but the ball and hunger: the stories that can’t be changed are the ones that nobody tries to change.

Third season, 1986-87. Something is different. Diego returned from the World Cup in Mexico, from the goal against the English, from the Cup lifted at the Azteca. He returned being the best player on the planet. It is not debatable, nor is it an opinion; it is a fact that even sports journalists have to accept.

But there’s something more. Diego is angry. Not the kind of anger that explodes, but the other kind: the kind that’s kept hidden, the kind that’s used up. Three years of hearing he can’t, three years of reading that his body isn’t enough, three years of promises he still hasn’t kept. Diego is ready to end it all.

First match: Brescia. Napoli wins 1-0. Diego scores the goal.

Second match: Milan. The great Milan. Diego scores two goals. Napoli wins 2-1.

Third match: Juventus, the Giant of the North. The match ends in a draw, but Diego makes a play that nobody forgets.

He takes the ball in his own half. He passes to one, to two, to three, to four. Five Juventus players are on the ground or looking the wrong way. The shot hits the post. The Turí stadium, full of Juventus fans, falls silent. Not from sadness, but from astonishment.

The season progresses. Napoli wins and wins and wins. Diego doesn’t just score goals, he does things that nobody understands. Passes that reach places that don’t exist, movements that defy logic, plays that seem choreographed but happen in the moment.

The toughest defenders in Italy absorb everything. They kick him, they push him, they grab him, they insult him in dialects that Diego doesn’t understand but whose meaning is clear. Nothing works. Diego receives the blows, gets up, continues.

The sports journalists no longer write about his body; now they write something else: “Maradona is from another planet. Maradona is doing the impossible.” Diego reads those articles. He keeps them with the others, the old ones and the new ones, in the same box. Opinions change. The people who criticize you are the same ones who applaud you later. The only thing that doesn’t change is what you do on the field.

May 10, 1987. Napoli plays against Fiorentina. If they win, they are champions.

Diego didn’t sleep outside that night. He spent the night thinking about his father, Don Diego, the man who worked in a bone mill to feed him. The smell of that work lingered on his clothes, on the worn hands that caressed him when he came home.

He thought of Villa Fiorito, the mud streets, the tin house, the matches played barefoot because there were no boots. He thought of Naples, of this city that looks so much like where he lived, of these people who look at him as if he were a god, but who don’t need a god. He needs someone who doesn’t laugh.

The match begins. Sa Paolo is impossible. The noise drowns out anything Diego might have heard. There are people crying in the stands and the match has only just begun. Fiorentina defends with everything they have. Eight men behind the ball. They didn’t come to win, they came to prevent history from changing.

Diego receives, passes, moves, receives again. The goal doesn’t come.

First half: 0-0.

In the locker room, silence. Diego looks at his teammates. He sees the fear in some of their eyes. The fear of being so close and not achieving it. The fear of continuing to be the ones who always lose. He stands up.

—Listen—everyone looks at him—. Outside there are 70,000 people who have waited their whole lives for this day. And there are millions more in the city, in the south. People who thought they could beat anyone.

Pause.

—Today we proved them wrong. Not tomorrow, today.

He enters the field. Minute 55. Diego receives the ball near the area. Three defenders surround him. There is no space, but Diego doesn’t need space, he needs time. And time always belongs to him.

He turns. The ball is perfect for his left foot. The defender extends his leg. Too late. The shot goes out. Low, to the corner. Goal!

Diego runs towards the stands. He doesn’t know what to do with his arms. He’s never felt anything like this. The stadium isn’t making noise, it’s doing something else. Something between a scream, a cry, and an earthquake.

The match ends 1-1. Napoli are champions for the first time in history.

What happens next can’t be described, only told. Naples doesn’t celebrate. Naples loses its mind. The streets are filled. Thousands, hundreds of thousands, shouting, crying, hugging strangers as if they were family. Cars can’t circulate. It doesn’t matter, nobody wants to go anywhere.

The celebration lasts a week. Seven days. The shops close, the offices close, the city stops. In the poor neighborhoods, people bring their televisions out into the street, watch Diego’s goals again and again. Each time they shout as if it were the first time.

In the Naples cemetery, someone put a sign on a tomb. The sign says: “You don’t know what you missed.”

Diego walks through the streets. He can’t move forward. Every meter there’s someone who wants to hug him, who wants to touch him. An old woman grabs his face with both hands, tears in her eyes. She says something in simple Spanish that Diego doesn’t fully understand, but he understands enough. She’s telling him that now he can die in peace. Qυe vio lo qυe пυпca creyó qυe iba a ver: qυe el sυr le gÿó al пorte, qυe los pobres le gÿaro a los ricos, qυe los пadie le gÿaro a los todos.

Diego is crying too.

In the world of sports, the newspapers had no choice but to admit what happened. Napoli were champions. Maradona accomplished the impossible. The south conquered the world of sports. The journalist from Milan, the one in the gray suit, the one who wrote “too short, too fat” three years ago, writes something different:

“I was wrong. We all make mistakes. Maradona is not a footballer. He is something that football has seen and probably will not see again.”

Diego reads that article. He keeps it with the others. Not as a trophy, but as a reminder that opinions are just noise. That the only thing that matters is what you do when everyone says you can’t.

Years later he asks him what winning that league meant. Diego remains silent. Then he says:

—In Barcelona I was a player. In Naples I was Diego. The people of Naples didn’t love me for the goals. They loved me because I was one of them, because I came from the same mud, because I knew what it was like to be looked down upon.

Pause.

—When I arrived they said I was too short, that my legs were too short, that my body wasn’t that of an athlete—he touches his temple—. I was right. My body wasn’t that of an athlete—he touches his chest—. But football isn’t played only with the body.

Long silence.

—The game is played here and here. And if you’re really hungry, the centimeters don’t matter a damn.

Today, more than 30 years later, Naples still has murals of Diego on every corner. There are still children who suffer with his name. There are still old people who cry when they talk about that May of ’87. The stadium is no longer called Sa Paolo, it is called Diego Armando Maradona Stadium.

Napoli won other titles later, but it still means what the first one meant. Because it wasn’t just football. It was the south against the port, the poor against the rich, the nobody against everyone. It was a 1.65m guy proving that greatness isn’t measured: you either feel it or you don’t. And in Naples, you still feel it.

If this story touched your heart and you lived through that era, tell me in the comments where you were when Napoli became champions. We want to know.