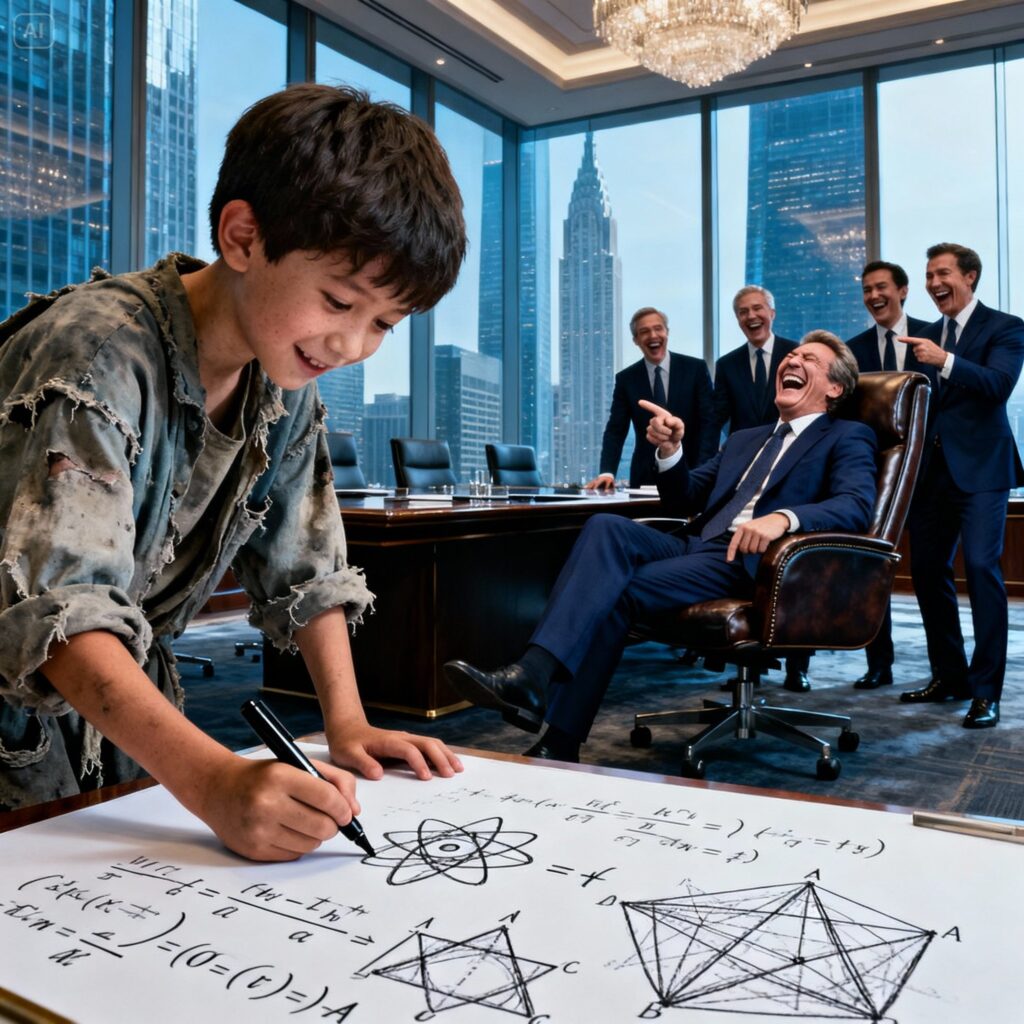

“Your calculations are wrong…” said the poor boy… The millionaire laughed… but he was also surprised.

“The numbers don’t lie.”

Roberto Santillán adjusted his Italian silk tie and looked again at the whiteboard as if it were a mirror that always reflected his point. There they were: perfect columns, clean arrows, percentages underlined in blue marker. He had rehearsed that presentation for a week, and that morning—in the boardroom on the 23rd floor of a skyscraper in Santa Fe—he was ready to close the biggest deal of his career.

—With this expansion —he said, pointing to the total— we are talking about fifty million pesos in initial investment and a projected return of seventeen percent.

To his right, his assistants nodded with strained smiles. In front of him, three Japanese investors watched silently, impeccably dressed, attentive. The eldest, Mr. Takeshi Yamamoto, carried a small notebook and a pen that he kept twirling between his fingers. The youngest, Kenji Sato, was all eyes.

Roberto took a deep breath. It was time to close the deal, to sell the dream: shopping centers, residential complexes, a brand that was multiplying across the country. His company, Grupo Santillán Desarrollos, had started in a tiny room with a borrowed desk. Now, the numbers on the whiteboard promised the next leap.

And then, a child’s voice—fine but firm—cut through the air.

—Your calculations are wrong.

The silence fell like a door slamming shut.

Roberto blinked, incredulous. He turned slowly, searching for the prank, the hidden camera, the reckless employee. But it was no prank.

Standing in the doorway was a boy of about twelve. He had messy brown hair, worn-out sneakers, and a backpack that seemed bigger than him. He was holding an old notebook with folded pages and a chewed-up blue pen.

The Japanese men looked at each other. Yamamoto murmured something in Japanese. Roberto felt a heat rise to his neck.

“Who are you?” he asked, trying to make his voice sound calm, even though his irritation was already sharp.

“My name is Mateo Hernández, sir,” the boy replied without looking down. “I’m the son of Doña Celia, the lady who cleans here. And… those numbers are going to cost you a lot of money.”

Roberto let out a loud laugh, more out of reflex than genuine humor. His assistants laughed too, nervously, like someone clapping to drown out thunder.

“Look, kid,” Roberto said. “Do you know how much a meeting like this costs? These gentlemen came all the way from Japan to evaluate my project. We don’t have time for… crazy ideas.”

“It’s not a coincidence, sir,” Mateo insisted, taking a step forward. “You multiplied 127,000 by 394, but you wrote 50,038,000. It should be 50,138,000. That’s a difference of one hundred thousand pesos.”

Laughter died in the middle of Roberto’s chest.

He stood still. He turned toward the blackboard, searching for the mistake like someone searching for their own lie.

“Impossible,” he thought. His team had checked everything.

Mateo opened his notebook as if it were a file.

“And on the third line,” he continued, “when he added up operating costs, he forgot the 2.3% administrative fee that was on the previous page. I saw that fee on a paper they printed yesterday.”

Roberto felt a chill in his stomach. How on earth did that kid know about internal documents, previous versions, rates that didn’t even appear in the final presentation?

“Can we verify?” Yamamoto asked in slow, clear Spanish.

Roberto swallowed hard. He couldn’t hesitate.

“Of course we can check,” he said, walking to the desk. “But my calculations are correct. The boy probably saw some random numbers and…”

He typed into the computer’s calculator. The silence in the room became heavy, almost palpable.

One second.

Other.

Roberto turned pale.

“No…” he murmured, recalculating. “It can’t be.”

Mateo looked at him without mockery.

—That’s wrong, isn’t it?

Roberto looked up and met the investors’ gaze. There was no anger, but a quiet alertness: the kind of look that assesses risks without needing to raise its voice.

“It was… a typo,” Roberto stammered. “We corrected it and carried on.”

Mateo tilted his head, as if asking something obvious.

—Do you want me to show you the other mistakes too? I found five more.

This time nobody laughed.

Roberto felt that the reputation he had built over twenty years was beginning to creak through a crack the size of a child with a backpack.

“What other mistakes?” he asked, forcing his composure.

Mateo approached the blackboard and pointed to the upper right corner.

—Here he calculated a growth of fifteen percent annually for five years, but he used simple interest, not compound interest. With compound interest, the result changes… it’s a difference of more than two hundred thousand pesos.

Roberto checked. Correct.

Mateo pointed to another line.

—And here he added the import costs twice: on line seven and again on line twelve. That’s eight hundred and ninety thousand counted twice.

Roberto felt sweat trickle down his back. His accountants, his engineers, his finance director… how could they have missed that? How could a child see it so clearly?

“How did you learn this?” Roberto asked, no longer in a scolding tone, but with genuine surprise.

Mateo shrugged.

—I like math. I wait for my mom here when she’s at work… and there’s a private school across the street. From the courtyard, you can see the math classroom blackboard through a window. I stay behind a tree and… listen.

The image struck Roberto in a way he hadn’t expected: a child learning from the outside, stealing knowledge from the world through a crack.

Yamamoto stood up, walked to the blackboard, and silently checked. Then he asked for Mateo’s notebook. The boy hesitated for a moment, looking at Roberto. Roberto nodded, defeated.

Yamamoto flicked through the pages. His expression slowly changed from caution to astonishment.

“These calculations… are correct,” he finally said. “And very well organized. Where did you learn financial projections?”

—I don’t know what “projections” means —Mateo answered honestly—. I only know that if money comes in and money goes out… you have to add it up properly, because otherwise, in the end, you won’t have enough.

The simplicity left everyone speechless.

Roberto felt a strange humiliation: not the kind that makes you angry, but the kind that cleanses you.

“Mateo,” he said, taking a deep breath, “can you help us correct the blackboard?”

The boy took the marker and confidently erased the numbers. His handwriting was surprisingly clear and neat. When he finished, he stepped back as if nothing had happened.

—List.

Yamamoto checked line by line. He nodded.

—Perfect. That makes the project make sense.

Roberto should have felt relieved, but he could only think of one other thing: if a child saved his presentation today, how many times had his company walked towards a precipice without realizing it?

“Where is your mom?” Roberto asked.

—On the eighteenth floor, sir.

Roberto asked them to call her. Minutes later, Doña Celia Hernández, about forty years old, entered, wearing an impeccable blue uniform, her hair tied back. When she saw her son there with men in suits, her face tightened.

“Did you send for me, sir?” she asked nervously.

“Your son helped us today,” Roberto explained. “He has an impressive talent.”

Doña Celia looked at Mateo with a mixture of pride and fear.

—I hope you weren’t disturbed, sir. I’m telling you to stay put…

—On the contrary— Yamamoto interjected. —He did us a great service.

Roberto observed the mother and son: the affection in a look, the dignity in their posture, and the wear and tear of a life of effort.

“Where does Mateo study?” he asked.

“At the public high school nearby,” Doña Celia replied. “He’s very studious, but… the school doesn’t have the resources to teach him more advanced things. He looks for them on his own.”

Roberto walked to the window. From there, he could indeed see the private school across the avenue. Children in expensive uniforms were going in and out with new backpacks. And, behind a tree, he imagined Mateo, still, learning from the edge.

He returned to the table.

—Mateo—he said—. Would you like to study mathematics seriously, with teachers who can take you further?

The boy’s eyes shone, but he looked at his mother first.

—Yes, sir… but my mom can’t pay.

Roberto listened to himself before thinking about it too much.

-I can.

Doña Celia tensed up, alert.

—In exchange for what, sir?

The question stung, because it was fair. Roberto had lived in a world where nothing was free.

“In exchange for your son not having to learn in secret,” she replied. “And… yes, I’d also like him to come some afternoons to review math. Not as an employee. As support, with supervision. Without taking him away from his school. And I’ll pay for private school and a tutor.”

Yamamoto took out a card.

—Ms. Celia, our group also has scholarships for talented young people. Consider that option as well. Talent like that… is rare.

Roberto felt, for a second, an absurd pang of competition. Then he was ashamed. It wasn’t a contract; it was a child.

When mother and son left, Mateo turned around in the doorway.

—Mr. Roberto… can I tell you something?

—Dime.

—You should also review the large shopping center project. Yesterday I saw a document on the secretary’s desk… and the numbers didn’t match the size of the land on the map.

Roberto felt like the blood had drained from his feet.

That shopping center was worth more than one hundred million pesos.

That night, Roberto barely slept. He summoned the finance director, the engineering department, anyone he could. And at nine in the morning, when Yamamoto returned with his team, Roberto already had the report in his hand… and an expression he hadn’t used in years: genuine concern.

“We found inconsistencies,” Roberto admitted. “And Mateo was right.”

Mateo opened his notebook.

“According to the document it said fifteen thousand square meters… but on the scale of the plan it looks less. I calculated it was about twelve thousand five hundred.”

The finance director, a man with two master’s degrees, was speechless.

“How did you calculate that?” he asked, incredulous.

—With the scale of the plan —Mateo replied—. And a ruler.

Yamamoto tilted his head, interested.

—Can we go to the site?

Roberto hesitated. It wasn’t protocol. But then again, it wasn’t protocol for a child to save the company twice.

—If Mrs. Celia agrees… let’s go.

An hour later they were on the outskirts. Developing land, signs advertising “Upcoming Capital Gains,” dust, and sun. Mateo got out first, counting steps, observing angles. He took out a small measuring tape.

—My mom gave it to me —he said—. She told me that a man should know how to measure well.

For an hour he patiently measured the limits. The adults followed him, silent, as if they were students.

“Okay,” he finally said. “It’s 12,430 square meters, not fifteen thousand.”

The silence was deafening. If the plot of land was smaller, the design wouldn’t fit, costs would skyrocket, and the project would fall apart. And the worst part: someone had inflated the figures. A mistake? Or something more?

Back at the building, Roberto locked himself in with his team.

“From today onward,” he said, “no project will be approved without independent verification. No more ‘trusting it just because it’s on paper.’ And we’re starting by investigating who gave us false measurements.”

Far from withdrawing, Japanese investors surprised him.

“In Japan,” Yamamoto said, “we value humility and continuous improvement. Today you accepted corrections and changed the process. That… gives us confidence.”

Then came the second surprise:

“We want Mateo to participate in the verification process,” Yamamoto added. “Not as a worker, but as a junior consultant, under supervision. His perspective has been… extraordinary.”

Doña Celia squeezed her son’s hand.

“That she doesn’t lose her place in school,” she said firmly. “That’s the first thing.”

“That’s the first thing,” Roberto repeated, looking at her respectfully. “And I swear on my name.”

The following weeks changed everything. Mateo continued attending his public high school in the mornings. In the afternoons, he took classes with an advanced math tutor: Professor Miguel Salgado, a retired engineer who, on the third day, said:

—This kid doesn’t just solve problems: he understands them. As if the numbers were speaking to him.

At the company, Mateo reviewed calculations in a small office, always accompanied. At first, some engineers resisted him. Then, when Mateo saved millions by correcting an impossible design, the resistance turned into respect.

One day, Roberto found him looking out the window.

“What do you think?” he asked.

Mateo shrugged.

—It’s strange. Before, I used to watch classes from outside. Now I’m inside… but I feel like there are still a lot of kids over there, behind the tree.

That phrase stuck in Roberto’s mind.

Little by little, what began as a “fix” grew into something bigger. Roberto created a program with public schools to identify talent: mathematics, technical drawing, logic. He called it the Open Windows Foundation, after the boy who learned by looking through one.

Mateo was the first to help choose interns. He didn’t do it as a “genius,” but as a colleague. He told them:

—It’s not magic. It’s practice. And asking questions without shame.

The day the first eight children arrived at the new educational workshop in the building—a room filled with blackboards, books, and rulers—Doña Celia wept silently. Roberto, who had only ever cried over stock market failures, felt a strange lump in his throat: pride in something money couldn’t buy.

Months later, in a simple ceremony, Mateo handed Roberto a folded piece of paper.

It was a handmade “certificate”, with numbers drawn on the edges.

“To the best boss and mentor. Thank you for listening to me when I was just a kid.”

Roberto couldn’t find the words. He just hugged him. An awkward hug, the kind a man used to shaking hands with, not holding stories.

“Do you know what’s the strangest thing, sir?” Mateo whispered in his ear. “That day I thought I was going to run.”

Roberto swallowed hard.

“And I thought you came to humiliate me…” he confessed. “It turns out you came to save me.”

The happy ending didn’t come with applause in a boardroom, but with something quieter: a change of course.

Two years later, Grupo Santillán Desarrollos was still growing, but with real audits, site visits, and teams that no longer took offense when someone pointed out a mistake. Yamamoto and his group increased their investment, not only for profitability, but also because of the educational model the company was promoting.

Mateo, now fourteen, sometimes traveled to Guadalajara or Monterrey to inaugurate new program locations. And every time an adult called him a “genius,” he would reply the same way:

—No. I only had a mom who taught me not to give up… and a man who decided to listen.

Roberto, for his part, understood something that wasn’t on the board: that true prestige wasn’t about “not making mistakes,” but about correcting them in time, with humility, and opening the door for others to enter.

And one afternoon, as he watched from his window the children from the program leaving with books under their arms —without hiding behind any trees— Roberto knew that, for the first time in his life, he had built something more important than buildings: opportunities.